List of Translations

These translations are predominantly of lyrics by Takashi Matsumoto, originally of Happy End (all Matsumoto lyrics are marked with the symbo...

July 22, 2023

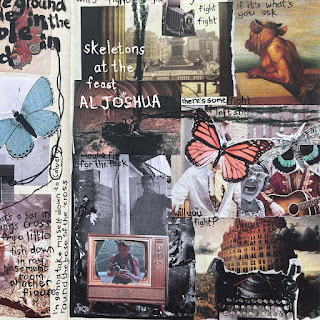

Skeletons at the Feast

May 28, 2023

Al Joshua from way long ago...

"Francis Bacon said he wanted his paintings to assault the viewer’s nervous system, and so return them back to life and consciousness more violently. I’m just trying to do that for myself. I’m looking for images and sounds that fray my nerves. Disturb, confuse and provoke myself is exactly what I want to do. Because it wakes me up and brings me back to life. And if it does this for me, then it will for a few other people too. Out of twenty people, nineteen might not like us, but for one person it will ring out like the right note being played in the right room and suddenly resonating."

(from an early 2009 interview preserved online. Orphans & Vandals were playing live but the album wasn't even out yet ... speaking of albums that at this point are out: remember, Skeletons at the Feast)

March 16, 2023

The baffled explorer's springtime report

In the past twelve months, I’ve had the good fortune of finding my way to not one, not two, not even three or four, but five brilliant songwriters. In a great year I make two such discoveries, tops.

In the case of Pain of Salvation’s Daniel Gildenlöw, I had an overdue awakening to the excellence of an artist I’d long treated with skepticism. I’ve detailed my road into Daniel’s arms elsewhere, but I want to note that watching the long and beautiful documentary series I Set Myself on Fire, which covers the making of Road Salt and some of the touring done on its behalf, helped. In it, Daniel is vulnerable, honest, funny, charismatic. The devotion to band and craft that he displays helped me learn to respect the albums I don’t love (the early stretch, up to and mostly including 2004’s “BE”), but sheer awe overcomes me once that dedication collides with music I can’t really imagine sounding better than it does, or being better-written than it is (2007’s Scarsick on).

Then there's Ragnar Zolberg, who co-wrote the music on Pain of Salvation’s In the Passing Light of Day. Before his stint in Daniel’s band, Ragnar had a power-pop group called Sign (with an excellent so-far-final album, Hermd, in 2013) and a darker, quieter, more ruminative solo career. He continued to put out albums while he served as Daniel’s second/lead guitarist in Pain of Salvation, and so he has gone on doing—modestly, without fanfare—since leaving. As my journey through his discography has revealed, it’s all gold, from 2008’s The Circle (Darker Side) right through to last year’s Forest Lovesongs and Hjartastjaki.

Ragnar writes and sings with a fearlessness and directness that won my heart at once, and I really mean at once. Of Artistry, the first solo song of his I tried, had me captivated, in disbelief, before my first listen to it was over. His songs have made me cry God knows how many times. If it was from Neil Young that I learned how powerful an “unvarnished heart on sleeve” approach to lyricism and delivery can be, Ragnar revealed how vast and deep that kingdom really is.

I was shown more of the kingdom when, a few months later, a list of music recommendations by Colleen Kinsella of Big Blood included the Yoko Ono albums Fly, Approximately Infinite Universe, and Feeling the Space. Big Blood’s 2017 album The Daughters Union is dedicated to Yoko, and on 2020’s Do You Wanna Have a Skeleton Dream?, 11-year-old Quinnisa, the band’s occasional third member and perennial firebrand, named Yoko Ono alongside Joan of Arc as someone who “changed the century.” Colleen’s 2022 list got me investigating the individual albums, whereby I learned that Fly and Approximately Infinite Universe are double albums. It’s usually when I discover that some intriguing artist I’ve been investigating has made a double album that I commit to giving them, and it, a proper try. So with Yoko. By the end of Side A of Approximately Infinite Universe, my mind was in splinters. By the end of Side B I was completely won over.

That was autumn. Come winter, I fell in turn to Richard Dawson, having stumbled on the cover art to The Ruby Cord in the week of its release and gazed at it awhile in that "Oh, right on!" kind of way. Reading up, I learned it was a double album. Alright then. I also realized that I had previously read intriguing reviews of Dawson releases (Peasant, Henki), and played a track or two each time, but things hadn’t clicked. Time to try again, because reviews of The Ruby Cord (mixed reviews, no less) made it sound phenomenal. And it was. I started with The Fool. Loved it. Went on listening in order. Loved the gentle Museum and especially its poignant, level-toned catalogue of the photographs on display. I was floored by the next song up, The Tip of an Arrow, with its gorgeous Joe Hisaishi-esque verses and unabashedly heavy metal (via folk) refrains. And the album closed with a song that made me think of Big Big Train. I think the sequence of my thoughts about the Big Big Train/Horse and Rider connection would have gone something like this: "How could that even...? What?! Too good!!!"

So then of course it was right back to Track 1, the 41-minute, LP-length opener, Disc 1 of a double album in the form of a single song: The Hermit. One of the best songs ever, as it turns out: a story that starts with a dream, awakes into the quotidian and not exactly lonely present, gazes backwards in a long and riveting, mostly a capella flashback, and concludes with a holy vision of the bloody center of life, suffering, and death.

Research showed that Richard Dawson has a band (Hen Ogledd) with, ahem, a double album (Free Humans). The album opens with the wild and evocative masterpiece Farewell (those lyrics, good lord! I mean, the thermal baths? and the sadness! and the bassline!). What exit did I have? And Crimson Star? "We were naked! We were naked!" But while those were both primarily Richard compositions, the contributions of his bandmates proved that, evidently, they were mad geniuses as well. Thus on, also, to Bulbils...

And now, with a mere month to go before my awakening to the splendor of Gildenlöw and Zolberg turns a year old, the doors of a fifth hidden palace have opened to receive me, and here I am, already a diehard fan of Magnolia Electric Co. How did I not find, and fall for, Jason Molina earlier?! Greatness always seems blindingly obvious after the fact. How, I wonder afterwards, could there have been a time when I was into Neil Young and Bob Dylan, but not yet into Brian Eno? How could I have spent so long adoring the Frusciante-helmed Red Hot Chili Peppers albums without delving into his solo discography? And how is it that, given my already multi-year interest in the generation of songwriters born in the 1970s, I found my way to the likes of Chadwick Stokes, Ned Collette, and James Jackson Toth, even (through the Vic Chesnutt/Undertow Orchestra connection—though I also, unwittingly, saw him drumming for Monsters of Folk at their Beacon Theatre concert in 2009) brushing up against Molina collaborator Will Johnson, but skipped ignorantly past the lighthouse that is Molina himself?

But all to its rightful season, of course. If you gathered every pearl on your first plunge, where would you find the time to live with your discoveries, to learn from them, to be nurtured and hallowed and remade by them? It would be like trying to enjoy the gentle, patient rolling of a mountain stream when you’re standing under a waterfall.

February 17, 2023

Skeletons at the Feast 2/17/23

On this February day, a new Al Joshua record has come. It is called Skeletons at the Feast and it's 75 minutes long, which makes it proper double-LP length: a full four-sided affair, beautifully sequenced. Buy it on Bandcamp and get the FLACs, or stream it if you must, but listen. Be lifted, be muddied, be purified, be puzzled. In any case, listen. Listen to it in full, listen to it often, listen to it carefully, then listen to it again. Let your memories, your thoughts, your sleeping, your dreaming, your waking, your walking melt into Al's melodies and words, into the shimmer and cacophony of the band. Just listen. Let it take root in you as it has, and as it yet will, in me.

"Finally awake. This time really, truly, completely awake."

-

These translations are predominantly of lyrics by Takashi Matsumoto, originally of Happy End (all Matsumoto lyrics are marked with the symbo...

-

Ragnar Zolberg, one of the greatest songwriters of our time, made his name in his native Iceland as the frontman of Sign , then reached a wi...

-

And here we are. The cat is out of the well. My favorite Bob Dylan song is Pressing On, as it has been since the evening I first heard it, l...